|

| Andy Tattersall |

Academia has become increasingly reliant on third-party tools and technologies to carry out many of the processes throughout the research lifecycle. But there are genuine concerns about the sustainability of some of these tools and what the implications would be for users in the event they were discontinued. Andy Tattersall suggests a series of straightforward questions researchers should ask themselves before choosing a new technology for use in their research. Can you export your content? Is there an alternative? After all, there is no guarantee your favourite tool will still be around tomorrow.

Academia has not always been good at adopting new technologies to aid research and teaching. Even a tool as seemingly popular and simple to use as Twitter has been received with some anxiety and trepidation within the scholarly community. There are various reasons for the slow uptake of new technologies, something not exclusive to the academic community, as captured in Everett Roger’s Diffusion of Innovations. Technology continually changes and the pressures of keeping up with it can actually cause inertia and some to bury their heads in the sand rather than engage with the changing environment. There are genuine concerns about the sustainability of tools we rely on in the academic community, with no guarantee that popular tools like Google Scholar or Twitter will be with us this time next year.

Adopting technologies that eventually cease business

There are several examples of really useful tools to have been accepted by the academic community only to pull down the virtual shutters for good. It can be quite depressing to have invested time and energy in mastering a tool only for it to disappear offline. This may happen for a variety of reasons, such as a lack of investment (financial or development), slow uptake, or the founding individual moving onto a new venture. Those in academia want solid, factual reasons to utilise a new tool; if the one they currently use works fine, why switch to another they haven’t heard of? It can be like the problem of buying a new laptop: why purchase one now when you could buy one with double the processing power for the same price a year later? Sadly that attitude means you end up not moving on at all. Academia is about finding answers to problems and learning from previous mistakes – surely the same should apply to the very tools we use to achieve better outcomes?

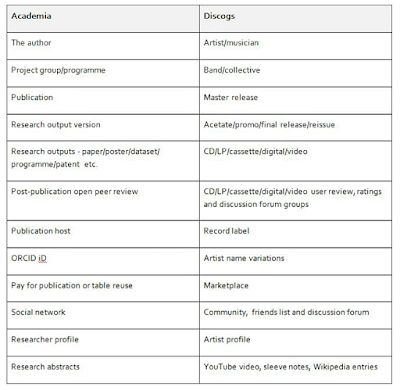

There are several issues around adopting technologies to carry out, communicate, and analyse research, issues further complicated by the duplication of platforms or providers’ expansions into new areas of business. Take Mendeley, for example, which started as a social network and reference management tool but has since expanded into a data-hosting and a funding-search service.

The sad demise of useful platforms

Google Reader, PageFlakes, Readability, Silk and Storify have all ceased business in recent years despite demand for their services. In some cases this can be problematic for users as they have invested great amounts of time in curating their own content, particularly so in the case of personalised dashboard PageFlakes or data visualisation site Silk. Thankfully, for most of the aforementioned tools there were suitable alternatives and useful sites like alternativeTo, which directs users to similar options. In some cases the provider itself even pointed towards an alternative, such as Readability which used its front page to direct users to Mercury Reader. Others such as Storify proved more problematic, with no immediate like-for-like tool obviously available and Wakelet seeming the best alternative.

Choosing the right tool for the job

For anyone working with academics to adopt new tools, or for those more proactive academics wishing to explore new ways of working, there are several questions you should ask before adopting a new technology. For the most part these are straightforward and it is important to remember you may only use some technologies once.

- Is it intuitive to use?

- Is there an alternative?

- Can you export your content?

- What are they doing with your data?

- How often will you use the technology?

- Do you know anyone using this tool already?

- Has the technology been around for long?

- Who created the technology and who owns it?

- Are the developers on social media and how often do they post new updates?

Nothing lasts forever

Academia is becoming increasingly reliant on technology, especially third-party tools, to carry out certain research processes. This has long been the case, with tools such as Dropbox or YouTube offering more functionality than in-house institutional platforms. With more tools comes greater diversity and potentially more problems. There is no guarantee we won’t see another dot.com crash like that of 2000, and this time academia would also feel its wrath. Many platforms, especially niche academic ones, are run by just a handful of staff or even students. They may have investors expecting a return on their capital, families with mouths to feed, or office bills to pay.

Another strand to this debate is the thorny subject of open-source versus profit-driven platforms within scholarly communications, as discussed in previous posts by Jefferson Pooley and Mark Hahnel. Some academics may prefer the open, community-driven nature of open-source technologies, believing these to be more aligned with core academic values. Yet rejecting all commercial platforms could mean cutting off your nose to spite your face, with open-source initiatives often hamstrung by technical and financial constraints that make them unsustainable.

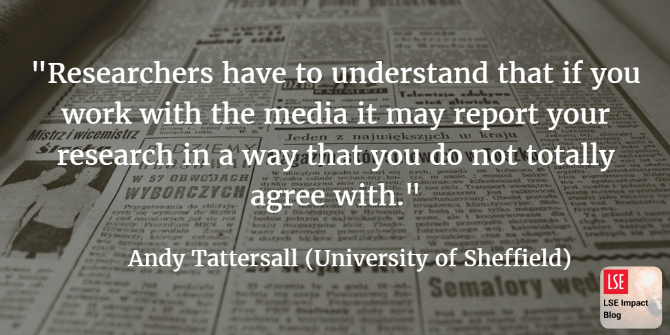

Academia’s increasing reliance on these platforms to undertake a multitude of tasks – including carrying out, communicating, and measuring research and its impact – requires greater dialogue around sustainability. It is likely that popular third-party platforms used by the academic community such as Twitter, Facebook, Slideshare, Google Scholar, and YouTube will be here for some time. But what about the smaller niche tools that have been essential in changing and enhancing how academics carry out their work? One only has to look at Google Reader, PageFlakes, and the many others that are no longer in existence. Academia needs to be flexible and adaptable to the changes brought on by the shifting sands of technology but also pay attention to the tools you love the most but which might not be around tomorrow.

Originally published on the LSE Impact of Social Sciences Blog

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License unless otherwise stated.